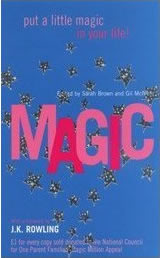

Rowling, J.K. Foreword. Magic: New Stories. Ed. Gil McNeil. London: Bloomsbury, 2002.

Magic is a collection of brand-new short stories, published by Bloomsbury

to raise money for one-parent families. The book is edited by Gil McNeil

and Sarah Brown, with a Foreword by JK Rowling, and written by eighteen

of Britain's most popular and exciting authors, including Andrea Ashworth,

Kate Atkinson, Celia Brayfield, Christopher Brookmyre, Lewis Davies, Isla

Dewar, Emma Donoghue, Maeve Haran, Joanne Harris, Jackie Kay, Gil McNeil,

John O'Farrell, Ben Okri, Michele Roberts, Meera Syal, Sue Townsend, Arabella

Weir and Fay Weldon.

Magic is a collection of brand-new short stories, published by Bloomsbury

to raise money for one-parent families. The book is edited by Gil McNeil

and Sarah Brown, with a Foreword by JK Rowling, and written by eighteen

of Britain's most popular and exciting authors, including Andrea Ashworth,

Kate Atkinson, Celia Brayfield, Christopher Brookmyre, Lewis Davies, Isla

Dewar, Emma Donoghue, Maeve Haran, Joanne Harris, Jackie Kay, Gil McNeil,

John O'Farrell, Ben Okri, Michele Roberts, Meera Syal, Sue Townsend, Arabella

Weir and Fay Weldon.

More information: http://www.bloomsbury.com/magic/

Purchase: http://www.amazon.co.uk/

Foreword

by J.K. Rowling

My involvement with the National Council for One Parent Families came about either very simply, or very circuitously, depending on how you look at it.

The simple version involved Andy Keen Downs, the charity's Deputy Director, sitting down in my habitually untidy kitchen, pulling out a sheaf of notes from his briefcase and embarking on what I'm quite sure would have been a marvellously persuasive, well-constructed and beautifully delivered speech.

"Andy," I interrupted, in that harassed voice which lone parents can often be identified, "you'd like me to be Patron, wouldn't you?"

"Well, we're calling it `Ambassador'," said Andy tentatively, cut-off mid-flow.

"OK, I'll do it," I said, "but could we please discuss the details on the way to school, because Sports Day starts in five minutes."

And so we discussed the National Council for One Parent Families while watching the egg-and-spoon races, a highly fitting start, I felt, for my association with a charity that is devoted to helping those parents whose lives are a constant balancing act.

The long version of how I became Ambassador includes my personal experience of single motherhood and my anger about our stigmatisation by some sections of the media. That story starts in 1993, when my marriage ended.

I was living abroad and in full-time employment when I gave birth to my daughter. Leaving my ex-husband meant leaving my job and returning to Britain with two suitcases full of possessions. I knew perfectly well that I was walking into poverty, but I truly believed that it would be a matter of months before I was back on my feet. I had enough money saved to put down a deposit on a rented flat and buy a high chair, a cot and other essentials. When my savings were gone, I settled down to life on slightly less than seventy pounds a week.

Poverty, as I soon found out, is a lot like childbirth -- you know it's going to hurt before it happens, but you'll never know how much until you've experienced it. Some of the newspaper articles written about me have come close to romanticising the time I spent on Income Support, because the well-worn cliché of the writer starving in the garret is so much more picturesque than the bitter reality of living in poverty with a child.

The endless little humiliations of life on benefits -- and let us remember that six out of ten families headed by a lone parent live in poverty -- receive very little media coverage unless they are followed by what seems to be, in newsprint at least, a swift and Cinderella-like reversal of fortune. I remember reaching the checkout, counting out the money in coppers, finding out I was two pence short of a tin of baked beans and feeling I had to pretend I had mislaid a ten-pound note for the benefit of the bored girl at the till. Similarly unappreciated acting skills were required for my forays into Mothercare, where I would pretend to be examining clothes I could not afford for my daughter, while edging ever closer to the baby-changing room where they offered a small supply of free nappies. I hated dressing my longed-for child from charity shops, I hated relying on the kindness of relatives when it came to her new shoes; I tried furiously hard not to feel jealous of other children's beautifully decorated, well-stocked bedrooms when we went to friends' houses to play.

I wanted to work part-time. When I asked my health visitor about the possibility of a couple of afternoons' state childcare a week, she explained, very kindly, that places for babies were reserved for those who were deemed 'at risk'. Her exact words were, "You're coping too well." I was allowed to earn a maximum of fifteen pounds a week before my Income Support and Housing Benefit was docked. Full-time private childcare was so exorbitant I would need to find a full-time job paying well above the national average. I had to decided whether my baby would rather be handed over to somebody else for most of her waking hours, or be cared for by her mother in far from luxurious surroundings. I chose the latter option, though constantly feeling I had to justify my choice at length whenever anybody asked me that nasty question, "So what do you do?"

The honest answer to that questions was: I worry continually, I devote hours to writing a book I doubt will ever be published, I try hard to hold on to the hope that our financial situation will improve, and when I am not too exhausted to feel strong emotion I am swamped with anger at the portrayal of single mothers by certain politicians and newspapers as feckless teenagers in search of that Holy Grail, the council flat, when 97 per cent of us have long since left our teens.

The sub-text of much of the vilification of lone parents is that couple families are intrinsically superior, yet during my time as a secondary-school teacher I met a number of disruptive, damaged children whose home contained two parents. There are those who still believe head-count defines a "real" family, who believe that marriage is the only "right" context in which to have children, but I have never felt the remotest shame about being a single parent. I have the temerity to be rather proud of the period when I did three jobs single-handedly (the unpaid work of two parents and the salaried job of teacher -- for I did eventually manage to take my PGCE, due to the generosity of a friend who lend me money for childcare). There is a wealth of evidence to suggest that it is not single-parenthood but poverty that causes some children to do less well than others. When you take poverty out of the equation, children from one parent families can do just as well as children from couple families.

My family's escape from poverty to the reverse has been only too well documented and I am fully aware, every single day, of how lucky I am; lucky because I do not have to worry about my daughter's financial security any more; because what used to be Benefit day comes around and there's still food in the fridge and the bills are paid. But I had a talent that I could exercise without financial outlay. Anyone thinking of using me as an example of how single parents can break out of the poverty trap might as well point at Oprah Winfrey and declare that there is no more racism in America. People just like me are facing the same obstacles to a full realisation of their potential every day and their children are missing opportunities alongside them. They are not asking for handouts, they are not scheming for council flats, they are simply asking for the help they need to break free of life on benefits and support their own children.

This is why I didn't need to hear Andy's well-rehearsed persuasive arguments on Sports Day. I had already made up my mind that it was time to put my money where my mouth had been ever since I experienced the reality of single-parenthood in Britain.

The National Council for One Parent Families is neither anti-marriage (nearly two-thirds of lone parents have been married, after all) nor a propagandist for "going it alone". It exists to help parents bringing up children alone, for example, in the aftermath of a relationship breakdown or the death of a partner, when children are faced with a new kind of family and one parent is left coping with the work of two, often on a considerably reduced income. It provides invaluable advice and practical support on a wide range of issues affecting lone parents and their children, and I am very proud to be associated with it.

The proceeds from the sale of this book will go towards the charity's Magic Million Appeal, whose funds will help maintain the broad range of services offered to lone parents who want nothing more than to pull themselves out of the poverty trap while bringing up happy, well-adjusted children. I would like to offer my very deepest thanks to the authors of the extraordinary stories that follow, and to everybody who, through buying this book, contributes to our appeal. You are offering hope to families who are too often scapegoated rather than supported -- families who could do with a lot less Dursleyish stigmatism, and a little more magic in their lives.

Original page date 22 April 2007; last updated 22 April 2007.